Recent travel articles in The New York Times and some magazines invariably depict some view of Monument Valley when extolling the glories of the Navajo reservation. Covering nearly 100 square miles, the area’s 30,000 acres became a Navajo Tribal Park in 1958. Before that, in the 1930s and 40s, John Ford made the place famous in his Hollywood movies. In fact, if we called Monument Valley iconic, we wouldn’t be wrong.As landscapes go, this one is rightly associated with Indian Country in people’s minds.

Its sheer scope, along with isolated mesas and buttes, was sculpted in the Cenozoic era when the region was under water. When the sea receded, what remained left behind were beds of sand. These hardened and compacted into the hundreds of stone formations so beloved of photographers.

Countless writers and journalists speak of the magic of the region, and how visiting this area clears their heads from every day cares and distractions. One personal note: after brain surgery in early 2002, I decided I wanted to go to Monument Valley for just those reasons later that year. What I had forgotten, however, is that it sits 4800 to 5700 feet above sea level. I had a wonderful time, except for the headaches!

With the national presidential campaign about ready to have its two candidates go face to face, one wonders what recognition Obama and Romney will make of their Native voters? Indians didn’t get the vote in America until 1924, four years after women received that right. Romney was governor of a state that swept most of its tribes away. As a Mormon, his fellows in faith have had mixed relations with Native peoples. President Obama’s profile about Native concerns is equally questionable. This year, the media has expressed interest in the voting of the Four Corners states in swaying the election. These votes include those from Indian Country. Many Natives in this region vote Democratic but come from conservative backgrounds.

Bruce Bernstein, the Director of SWAIA, has had a long and distinguished career in the world of Indian arts. His scholarship is top-notch. I recently reread a piece by him in an anthology, Native American Art in the Twentieth Century: Makers, Meanings, Histories. In doing research for my next book on Southwestern Indian bracelets, I found an article he’d contributed to the anthology on how the 1960s and 1970s provided new contexts for Indian arts. Bernstein pointed out the start of an international profile for Indian artists, including foreign exhibitions for selected individuals. He describes how changes in the American social and intellectual climate helped make Native American Studies an academic discipline.

My own education in the first half of the 1970s occurred too early to benefit from this. My dual major of art history and anthropology of the North American Indian (a mouthful) shows how great the emphasis on anthropology still was at that time. The creation of Native American Studies helped usher in a multidisciplinary — and interdisciplinary — approach to Native art production. Bernstein also wisely points out that the “traditional” arts with their handcrafted nature made them popular in America in general. Even their introduction into home decoration played a role we still recognize today.

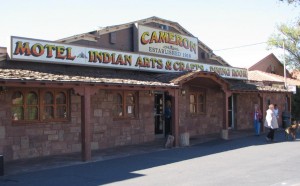

One of our favorite rides is from Cameron to the eastern entrance of the Grand Canyon at Desert View. The Cameron Trading Post has come to symbolize the best and worst of Southwestern souvenirs. The town and trading post are named after Ralph H. Cameron, a noted entrepreneur of the Grand Canyon’s attractions and one of the last territorial delegates from Arizona to the U.S. Congress. Cameron also became a U.S. senator from Arizona, which is enjoying its one-hundredth anniversary of statehood this year.

This portion of Highway 64 was originally made by the Fred Harvey Company so its famous “Indian Detours” could convey tourists to the Canyon’s South Rim. This great stretch of road climbs and drops 3000 feet in 35 miles.

We are rabbit owners and totally besotted over our pets. American Indians have a much more guarded view of these furry mammals. Rabbits are largely prey animals, and we realize this while admiring the beauty of handmade Hopi rabbits sticks. Rabbits aren’t worthy enough to be part of the six directions or serve as serious hunting fetishes. Nor do any Pueblo cultures salute them as possessing katsina-like characteristics. Nevertheless, Indians do understand one essential thing about rabbit nature. They are tricksters, not unlike Coyote. Rabbits do creep into some of the old tribal stories.

Back in the late 1980s we hit beginner’s luck and discovered a weaving of domestic rabbits by the great Navajo weaver Fannie Pete, known for her remarkable animal depictions. From time to time, rabbits pop up as motifs on jewelry and other Native arts. Navajo folk art depicts them as comical creatures, and then there is the classic children’s book, Ten Little Rabbits, with its cover of rabbits snuggled into Navajo serapes…

“Rabbit Boy” by Lansing – the perfect example of the trickster rabbit in Navajo folk art.

“Rabbit Boy” by Lansing – the perfect example of the trickster rabbit in Navajo folk art.

Southwestern Indian Rings

Southwestern Indian Rings

by Paula A. Baxter

Photography by Barry Katzen

Visit Amazon for its discounted price

With a fascinating variety of American Indian rings from the southwestern United States shown in more than 360 color photos, Southwestern Indian Rings

provides a design history of these rings, beginning with pre-contact artifacts and continuing through to contemporary artistic innovations.

The text surveys key developments in Native American ring design; materials and methods of construction; definitions for historical and vintage rings; master innovators; and the transition from craft to wearable art since 1980.

Shortly after the Civil War, Native American artisans began making silver rings set with turquoise, coral, jet, mother-of-pearl, and colored shell, adding lapis, malachite, onyx, and petrified wood over the decades. More recently, artisans began utilizing gold and such non-traditional settings as opals and diamonds, among others.

Works by Navajo and Pueblo artists are featured, although Apache, Northern Cheyenne, and Sonoran Desert Native jewelers are also included. A guide to valuation issues and resources is offered for collectors.

978-0-7643-3875-5

hardcover $34.99 (but Amazon is giving a discount)

8 1/2 x 11

160 pages

361 color photos

For the third time, we tried to visit Toadlena Trading Post and failed. We attempted two times back in the mid-to-late 1990s when we were doing our roving trading post visits. We found Two Grey Hills on the dirt road, but no luck when it came time to sight Toadlena. On our recent visit last month, we were traveling on Route 491 (former Rte. 666) from Gallup to Shiprock and back. We knew the turnoff was around Newcomb, we had our maps out, and there were some signs not far out of both Gallup and Shiprock. Yet we failed again.

The culprit, we realized, was the fact that New Mexico DOT is working on Route 491 in that area, doing bypass construction and road widening. Subsequently, the turnoff from 491 wasn’t indicated. We’ve been pretty excited about the work that Mark Winter and staff have been doing to make this 1890s trading post come alive again with weaving talent and the chance for the visitor to have an artful museum experience. Nevertheless, a well-placed sign at the turnoff would help everyone. Maybe the construction workers moved it. We’ll try to find this elusive trading post yet again on a later trip. In the meantime, if you plan to visit — get your GPS going!

We recently received a report from a usually reliable source about a practice that happens at the Inter-Tribal Indian Ceremonial, held in Gallup at Red Rock State Park. This event most often takes place the week and weekend before the SWAIA Indian Market in Santa Fe. The Inter-Tribal has had a rough patch related to funding, but is still considered one of the important shows in the summertime calendar of Indian arts. Native artists submit their work for judging and display, and the judges tend to be experienced Indian traders and regional experts.

It turns out that artists pay a holding fee to keep the judged art on display through the length of the Ceremonial; this fee also causes some of them to place an extraordinarily high price on a prize-winning piece in the hopes of not selling it at Ceremonial, since it can get a higher price as a result at the Indian Market or elsewhere. An award from the Ceremonial judges is a known boost in value for such a work.

The small-sized items produced for sale at Fred Harvey Company hotels, restaurants, and tourist outlets — like Desert View on the South Rim of the Grand Canyon — are amazingly popular and have kept their collectible nature. Prices were quite low, especially for manufactured goods, until this past decade. Collectors examining Fred Harvey objects such as jewelry are experiencing sticker shock these days. As more and more individuals have taken notice of a unique form of Americana, those small bracelets with stamps of horses and whirling logs or strands of turquoise shaped by Santo Domingo Indians, have seen a 20-35% increase in sale price.